- Home

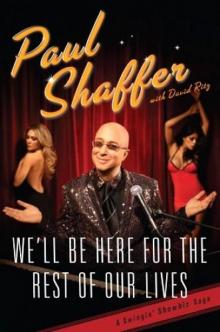

- Paul Shaffer

We'll Be Here For the Rest of Our Lives

We'll Be Here For the Rest of Our Lives Read online

For Cathy, Victoria, and Will

Contents

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

PRELUDE

Chapter 1 DYLAN AND ME

Chapter 2 TWO JEWS’ BLUES

Chapter 3 B3

Chapter 4 RUNNING INTO RAY CHARLES

Chapter 5 WITH YOUR KIND INDULGENCE…

Chapter 6 SHAFFER A-GO-GO

Chapter 7 DID YOU HEAR THE ONE ABOUT THE VENTRILOQUIST AND THE RABBI?

Chapter 8 HERE I COME TO SAVE THE DAY

Chapter 9 FRANK SINATRA WELCOMES ELVIS BACK FROM THE ARMY

Chapter 10 SWEET, SWEET CONNIE

Chapter 11 THE ALL-TIME GREATEST PUSSYCAT OF THE WORLD

Chapter 12 NIGHTS IN WHITE SATIN

Chapter 13 KEEPING NORTH AMERICA SAFE

Chatter 14 “YOU’VE SEEN THESE, THEN?”

Chapter 15 “WHERE ARE WE NOW?”…

Chapter 16 BLAME CANADA

Chapter 17 JILLY LOVES YOU MORE THAN YOU WILL KNOW

Chapter 18 “LOVE’S THEME”

Chapter 19 “WHICH OF THESE COFFEES IS THE FRESHER?”

Chapter 20 A BLACK CASHMERE COAT WITH A RED SILK LINING

Chapter 21 HOLLYWOOD SWINGING

Chapter 22 THE BRADY BUNCH, THE OHIO PLAYERS, AND MR. CHEVY CHASE

Chapter 23 PAUL AT THE GRAMERCY

Chapter 24 CATHERINE VASAPOLI

Chapter 25 THE BLUES BROTHERS!

Chapter 26 DIVIDED SOUL

Chapter 27 KING OF HAWAIIAN ENTERTAINMENT

Chapter 28 THE HEALING POWERS OF MR. BLACKWELL

Chapter 29 HOW BLUE CAN YOU GET?

Chapter 30 THE CALL THAT CHANGED IT ALL

Chapter 31 BLUES, BROTHER

Chapter 32 I’M NO HOMOPHOBE, OR HOW I CAME TO CO-WRITE “IT’S RAINING MEN”

Chapter 33 THE GIG OF GIGS

Chapter 34 MY ELVIS

Chapter 35 LOVING GILDA

Chapter 36 “KICK MY ASS—PLEASE!”

Chapter 37 TAKE MY LIMO, PLEASE

Chapter 38 VIVA SHAF VEGAS

Chapter 39 MEL GIBSON AND THE JEWS

Chapter 40 ON THE NIGHT SHIFT

Chapter 41 BAD TASTE

Chapter 42 FAMILY IS EVERYTHING

Chapter 43 WHAT KIND OF HOST AM I?

Chapter 44 THE GRINCH WHO RUINED CHRISTMAS

Chapter 45 PATRIOTISM AND RELIGION

CREDITS

acknowledgments

Paul thanks …

David Letterman, it’s an honor to take it to the stage with you every night—a true friend David Ritz, you are the answer to the question, “What is hip?” Daniel Fetter, without whom I wouldn’t know where “1” is Eric Gardner, wise and conscientious counselor; I couldn’t imagine a better manager Suzan Evans Hochberg, my favorite rock and roll lawyer chick Chris Albers, writer to the stars, labor negotiator; who says working for me doesn’t lead anywhere? Chris Schukei, news anchor, marketing genius; who says working for me doesn’t lead anywhere? Jann Wenner, your knowledge and loyalty are unwavering Phil Hordy, my good friend, thanks for my street and hooking up the Order of Canada David Smyth, for the gig that entitled this book Susan Collins Caploe, what a voice! Joel Peresman, the rock CEO with the movie-star looks Joel Gallen, talent by the gallon Bob Anuik, lead Fugitive who sang the hell out of “Jezebel” Frank De Michele, first bass man (Fugitives) Peter Demian, second bass man (Fugitives) who taught me “Stand By Me” Ian Rosser, third bass man (Fugitives), designed his own electric sitar—it’s a cool world Don Murray, original drummer (Fugitives) Tom Schiller, neither of us turned out to be gay Rhonda Coulet, sang beautifully at Belushi’s memorial Rita Riggs, turned me out as an eyewear addict Tony Reid, the ring-bearer on the unicycle Barbara Gaines, exec producer, Thanks for the Memories Maria Pope, exec producer, Dream Weaver Tom Leopold, the industry vet John Evans, dug “Love’s Theme” as well Lee Gabler, my buddy in the Area of Responsibility Jude Brennan, exec producer, still doesn’t know what “Act 1” is Michael Lichtstein, it’s his “Day in Rock” Danno and Laura Wolkoff, rock Cleveland Alan Cross, a funny, funny man John Sykes, a dear friend who gave me some unforgettable gigs Matt Roberts, supervising producer and lyricist extraordinaire Margo Lewis, agent/organist—what a combo! Rob Burnett, swingingest CEO Jill Leiderman, does it all Senator Marian “The Babe” Maloney, dear family friend Her Excellency Governor General Michele Jean, with deep respect Rob Cohen, for the Sammy plaque Gabrielle Lappa, honours with a “u” Charlotte Igoe, had a Hammond as well Lee Richardson, for slipping me into that reception line The Stangles, Jerry and Sheila, thanks for the support

David thanks …

Paul Shaffer, “King of ’em All, Y’all” Suzanne Herz Steve Rubin David Vigliano Peter Gethers Claudia Herr Stacy Creamer Emily Mahon Geoff Martin Helen Ansari Rob Kaufman My gang: Roberta, Alison, Jessica, Jim, Henry, Charlotte, Alden, James, Esther, Elizabeth, the great Pops Ritz and all the family, including Harry Weinger and Alan Eisenstock

1971–

The Brass Rail.

I’m twenty-one, and I’ve made it. I’m playing on Yonge Street, Toronto’s main drag, where clubs like the Zanzibar and the Coq d’Or feature rockers like Rompin’ Ronnie Hawkins and David Clayton Thomas. To be honest, though, the Brass Rail is a little farther up the street on a slightly less swinging block.

Doesn’t matter. I’m thrilled to be here and I’m thrilled to be providing musical accompaniment for the nightclub’s topless dancers. These girls may be a bit frayed around the G-string, but to me they’re simply irresistible. I’m also happy to see that many of my college pals, who have never before bothered to hear me play, are out in force. In fact, they’re so interested in my music that they’re sitting at ringside tables. As for me, I’m caught in an exquisite dichotomy: embarrassment versus erotic stimulation.

It’s a grind—literally for the girls and metaphorically for me. My grind is the stringency of the set requirements: seven straight hours, from 6 p.m. to 1 a.m., fifty minutes on, ten off. I bring on the dancers at the top of the set, when they do one number “covered,” then two topless. After a few tunes from the band, they return at the bottom of the set for more of the same. So at the end of this long and beautiful/awful night, it’s time to wrap it up.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” I intone, playing to my friends, “let’s hear it once again for the very lovely, extremely talented Brass Rail Topless Go-Go Dancers. The exquisite Donna. The enchanting Shanda. The delightful LaShana. The priceless Tiffany. And the irresistible Bree. We love them madly. Well, that’s about it for us. We are the Shaf-Tones. Please come back and see us. We’ll be here for the rest of our lives.”

Chapter 1

Dylan and Me

Bob Dylan was standing two feet away from me. It was the late seventies, and I was the piano player on Saturday Night Live. I was talking with his current producer, the legendary Jerry Wexler, as we watched Dylan rehearse his band. I was right where I belonged. Surely God had blessed me by putting me in this favored position. Only one problem: Dylan was wearing a huge cross.

So what was the problem?

A little background information: I grew up in an Orthodox synagogue. I also grew up at the end of Highway 61. My hometown of Thunder Bay, Ontario, Canada, is at the northern extreme of that storied road. Thunder Bay is where my close friend Wayne Tanner, one of the original Dylanologists, turned me on to the great singer/songwriter. His album Highway 61 Revisited was the Talmud to the Torah of my life. I learned Al Kooper’s high organ line and Paul Griffin’s piano part on “Like a ‘Rolling Stone” note for note, sound for sound. The keyboard combination helped define Dylan’s new sound. And the sound made me absolutely crazy. Then there was the certa

in knowledge that Dylan, the most important poet of our generation, was also a landsman. Bobby Zimmerman was a fellow Jew.

In the seventies, I had heard that Bob had returned to his Orthodox roots. Supposedly he was studying with a Hasidic rabbi in Brooklyn. Then came the rumors that our man Zimmy had ventured beyond the Old Testament into the New. I didn’t want to believe it. I clung to the notion that once they cut the tip, you’re always hip.

Yet there he was, onstage in Studio 8H at 30 Rock in the middle of New York City, singing “You Got to Serve Somebody.” And I knew damn well that “somebody” sure wasn’t Moses. I was bothered and bewildered. Dylan was bewitched.

“Can we lose the cross, Jerry?” I whispered in Wexler’s hairy ear.

“Oh, I wouldn’t say anything,” he said in a panic. “Bob takes this shit seriously.”

“I’m kidding,” I said.

But I wasn’t.

The rolling stone rolled on. The planet took several spins, and several worlds later I was amazed to find myself on nightly television as musical director of Late Night with David Letterman. Word came down that on this particular night there were to be two guests. The first was the flamboyant pianist beloved by audiences in Las Vegas, none other than Liberace. The second was Dylan. Liberace was there to cook, Dylan to play.

“Hey, Dave,” I said at the top of the show, “what a night! Liberace cooking? In my book, that cat always cooks. And Dylan—I’m shocked. Did you know he went electric?”

“Calm down, Paul,” Dave said.

After Dave and Liberace worked up a soulful soufflé, Dylan came on with a borrowed band. Nonetheless, his three-song set was powerful. His “License to Kill” killed. Afterwards, I couldn’t keep from knocking on heaven’s door. I had to bond with Dylan.

When I stuck my head in his dressing room, I saw that he was with his lovely and talented girlfriend, singer Clydie King.

“Hi, Bob,” I said and, offering Clydie a smile, quoted Dylan himself: “What’s a sweetheart like her doing in a place like this?”

Bob nodded in my direction. He didn’t say a word.

“You know, Bob, you grew up just 130 miles to the south of my hometown in Canada. We’re linked by Highway 61. And I gotta tell you something else, man. Just like you, I spent my growing-up years with my ear pressed against the transistor listening to those faraway southern radio stations. Just like you, I learned to love rhythm and blues. And hey, Bob, how about that Bobby Vee? You played piano with him, I could sing both parts to ‘Take Good Care of My Baby.’ We’re soul brothers.”

I waited for his response, but none came. He just seemed to be staring into space. But I kept going.

“When you sang Roy Head’s ‘Treat Her Right’ in rehearsal today, Bob, it sounded just great. I wish you’d record it.”

Finally Bob looked me in the eyes. I’d obviously made a connection.

“Paul, do you think you could introduce me to Larry ‘Bud’ Melman?” he asked, referring to the lovable nerd who was a running character on our show.

I thought Dylan was kidding.

But he wasn’t.

Years later, I encountered a different Bob at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction dinner. This Bob enthusiastically grabbed his guitar and joined the post-dinner jam. His fellow jammers that night were, among others, Mick Jagger, Tina Turner, George Harrison, Ringo Starr, and Jeff Beck. Bill Graham and I were running the thing together. In those years there were no rehearsals. The jams were completely spontaneous.

As a finale, I called “Like a Rolling Stone.” Dylan graciously took the mic and began to sing, backed up by Mick and Tina. After the second chorus, Bill came out and whispered in my ear, “Guitar cutting session.” He wanted the guitarists to play against each other. I set them up—first Beck, then Harrison, then all the others. The guitar riffs were stupendous, but now it was time to get back to the song. I looked at Bob and gestured toward the mic. He stared back blankly. He clearly didn’t know what to do.

I moved in next to Dylan, realizing I had to lay it out for him. He needed to sing. So instead of gesturing, I just whispered in his ear…

“How does it feel?”

Wow! I thought, I’m directing Dylan to sing his own song with his own lyric.

Then he got it. He went to the mic and sang with Zimmerman zest, “How does it feel…to be on your own…”

And with that, if you’ll forgive the pun, our poet laureate got us out of a jam.

Then came the Good Friday when Dylan crucified me, only to resurrect me on the Sunday. This passion played out on the stage of Radio City Music Hall. In those years we would sometimes broadcast a Letterman anniversary special. And for the tenth anniversary Dave wanted Dylan.

“Hey, Paul, Bob’s agreed to come on,” Dave said. “He’ll play with the all-star band you’ve put together. Who do you have this year?”

“Carole King, Steve Vai, Chrissie Hynde, Doc Severinsen, Emmylou Harris, the James Brown horns—and that’s just for starters.”

“I’d love for Dylan to sing ‘Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again.’”

“Not sure it’s enough of an anthem, Dave. This is going to be monstrous. Do you know ‘One of Us Must Know’ from Blonde on Blonde?”

“Not sure. Play it for me, Paul.”

I slipped in the disc and within two bars Dave stopped me. “No,” he said.

We went back and forth until we landed on the inevitable. It had to be “Like a Rolling Stone.”

“You call Bob,” said Dave. “You’re the one who has the rapport with him.”

“Right. Dylan loves me.”

Dylan was hard to find. He lives on the road but is never anywhere for more than a day. Finally, I tracked him down in some motel in Des Moines and placed a call. When I told him that we’d be honored if he’d play “Like a Rolling Stone,” he was lukewarm at best.

“That’s a little obvious,” he said. “There’s gotta be something else.”

“Dave and I really see ‘Like a Rolling Stone’ as our grand finale.”

The songwriter sighed. “It’s a big catalog, Paul.”

I was surprised to hear Bob Dylan sounding like music publisher Don Kirshner. Oh well, as an industry vet once told me, “It’s all show biz. Totie Fields, John Coltrane—they’re the same. Well, Totie could improvise.”

“Tell you what, Paul. I’ll be rehearsing my band in New York next week. Come by and we’ll kick some things around.”

When I showed up at the studio, Bob and the band were immersed in Paul Simon’s “Hazy Shade of Winter.” I’d later learn that Dylan dealt with writer’s block by playing other people’s songs. It loosened him up.

When they were done, he acknowledged me and indicated the piano.

“Let’s try ‘Rolling Stone,’” he said. I was pleasantly surprised. With the band behind me, I rose to the occasion. Paul Griffin would have been proud. Dylan was happy. It was on.

The next Friday, though, found me in something of a stew. Dylan had come to rehearse with my all-star band but, lo and behold, he needed to be gone before sundown. His long and winding spiritual road had led him back to Orthodox Judaism. He refused to play on the Sabbath. I had no time to waste. I placed him in front of the band and counted off. For reasons that were unclear, he refused to sing.

“Let’s go again,” I said.

This time he strummed his guitar a little, but nothing came out of his mouth.

I approached him gingerly. “What’s going on?” I asked.

“I don’t need this band to play my music,” he said. “Me, I got four pieces. That’s all I need. All this other stuff don’t make no sense.”

Panicked, I motioned to my assistant. “Get Dylan’s manager over here,” I ordered.

Jeff Kramer, Dylan’s man, was an old friend. I spoke plainly. “Bob hates the band, Jeff. I don’t know what to do.”

“Just keep going,” said Jeff. “He always does this.”

But when I ran the tune the thi

rd time, Dylan still stayed silent.

So with the sun setting in the west, I called it a day. “Good Shabbos, Bob,” I said as he left the stage. “See you tomorrow.”

His exit left me in a state of uncertainty. I couldn’t understand what was wrong. Carole King was wailing on that piano part. Steve Vai was channeling Hendrix on guitar. I was channeling Kooper on organ. What could be bad?

Saturday night arrived. We were to do a dress rehearsal before a live Radio City audience at 7 p.m., then the real show at 10. Lots of funny stuff in the first two acts. Then the third act: Bob Dylan singing “Like a Rolling Stone” backed by my superstar band.

Before Bob’s entrance for the dress, I got an idea. While the band warmed up on “Everybody Must Get Stoned,” I stood at his mic.

“Let me hear what Bob will hear,” I asked the engineer.

I heard very little. It turned out Bob’s monitor had nothing in it. The stage was so big, the hall so cavernous, all Bob had heard yesterday was a dull roar. No wonder he hated it. He couldn’t hear it.

Then I went to work. “Give him some drums,” I told the engineer. “Give him some bass. He needs to hear piano. Put some of my organ in there. Mix in a little guitar.”

I did the best I could with the time that I had. At least now he had a halfway-decent mix.

When it came time for him to sing, I held my breath. His mouth moved, and some of that wonderful reediness came out, but I’d have to say he gave me only 30 percent.

Between the dress and air shows, Chrissie Hynde took me to Dylan’s dressing room. If you’re going to see Bob, let a woman lead the way.

“Everything okay, Bob?” I asked.

“It’s sounding a little better,” he said.

“Will you be able to sing?”

“Long as you can play.”

Well, I did play. And so did the band. And, I’m happy to report, Mr. Dylan did sing. This time he gave me a more than decent 70 percent.

By the time I arrived at the after-party, Bob was already there. He and Chrissie had their guitars out and seemed to be in sync. I sat down beside him and asked, “How do you think it went?”

We'll Be Here For the Rest of Our Lives

We'll Be Here For the Rest of Our Lives